Which Productivity Puzzle?

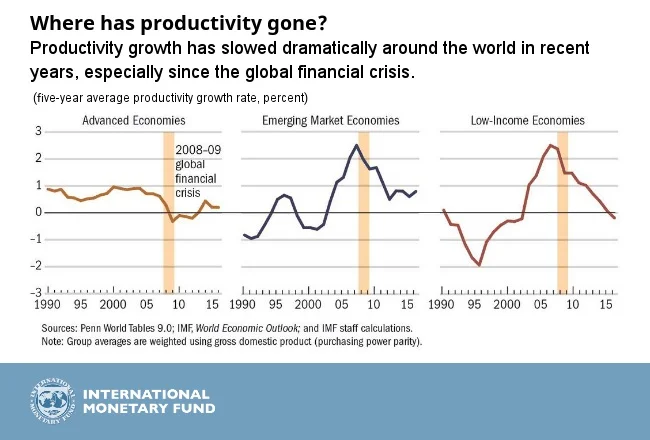

Productivity is the key driver of economic growth. It is the force that increases output of goods and services beyond what increased inputs of labor, capital and other factors of production like energy can account for. So growth in productivity increases income per head, the size of the pie available for distribution. And, as conventionally defined, the “Productivity Puzzle” is the unexplained decline in the growth of productivity observable over the past decade, through the recovery from the Great Recession triggered by the Global Financial Crisis of 2008. Here is the IMF’s picture for the advanced economies:

In fact, the decline in productivity growth has a longer history: over the past 30 years, with the exception of the uptick during the years of the great Dotcom/Internet Bubble of the late 1990s, productivity growth has slowed markedly.

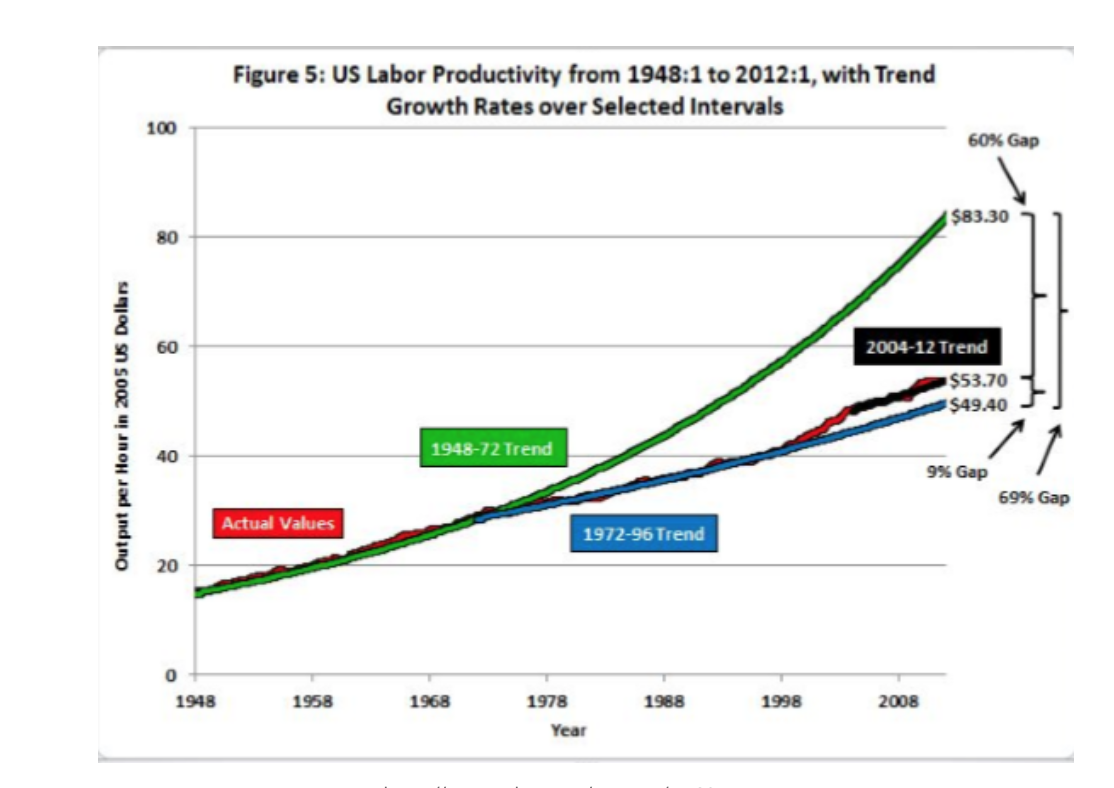

Post-war reconstruction, especially of the devastated economies of western Europe and Japan, was responsible for a rate of growth in productivity that was unsustainable. But in 2012, ignoring the one-off character of the 15 years to 1972 and focusing on the US, the distinguished economic historian Robert Gordon established himself as a leading techno-skepticist. In his provocative essay “Is U.S. Economic Growth Over?” Gordon graphically dramatized the divergence from the previous trend that began in 1972:

One mode of response to Gordon and to the data has been to focus on the potential mismeasurement of output in the increasingly digalized economy, since any such shortfall would automatically reduce the measured rate of growth in productivity. Thus, MIT’s Erik Brynjolfsson and Joohee Oh, note:

Over the past decade, there has been an explosion of digital services on the Internet, from Google and Wikipedia to Facebook and YouTube. However, the value of these innovations is difficult to quantify, because consumers pay nothing to use them.

But their estimate of the missing output is only $30 billion, barely a rounding error in a $18 trillion economy.

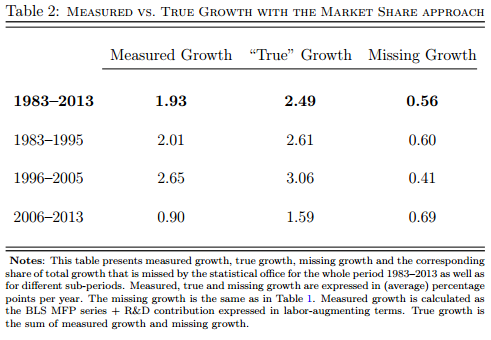

Recently, leading economist of innovation Philippe Aghion and colleagues have identified what appears to be a substantially larger source of under-measurement of productivity in the over-statement of inflation. Aghion and colleagues examine the process through which the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics accounts for the price of new products and services in their inflation indices by using the prices of already existing “comparable” offerings. Since new additions to output are most likely to be sold at lower prices, the result is to over-state inflation and to under-state growth of real output and, consequently, productivity:

Aghion, et. al., “Missing Growth from Creative Destruction”, p. 25

But the understatement of productivity growth captured by Aghion only amounts to 0.28 percentage points of the 1.75 point decline in the rate of real economic growth and productivity between 1996–2005 and 2006–2013.

Average Productivity Growth Defines the Wrong Question

All of this observation and analysis concerns the rate of growth of averageproductivity. With respect to income and wealth, we have learned from the late Anthony Atkinson and Thomas Piketty to look through the averages and evaluate the distribution. In this case, the focus on average growth in productivity across the whole economy be misses the point. Gordon himself opened the door to a radically different approach when he partitioned American economic history into three industrial revolutions as follows:

The first (IR #1) with its main inventions between 1750 and 1830 created steam engines, cotton spinning, and railroads. The second (IR #2) was the most important, with its three central inventions of electricity, the internal combustion engine, and running water with indoor plumbing, in the relatively short interval of 1870 to 1900. Both the first two revolutions required about 100 years for their full effects to percolate through the economy….The computer and Internet revolution (IR #3) began around 1960 and reached its climax in the dot.com era of the late 1990s, but its main impact on productivity has withered away in the past eight years.

Thus the IR #3 — the Digital Revolution through we are continuing to live — is truncated at half the lifetime that it took the first two IRs to generate “their full effects.” And its sole and transient contribution was the brief upturn in productivity growth during the dotcom/internet Bubble of the late 1990s.

Gordon the historian is, of course, correct. It takes time, lots of time for transformational technologies to deliver their full economic consequences. First, it takes time for novel inventions such as steam engines, electric generators and motors, digital computers and packet switches to be deployed ubiquitously through physical networks. And then it takes more time for the experimentation and learning by trial and error required to discover what the commercial applications of such innovations are.

It was some 50 years from the first railways in the 1820s to deployment of what Berkeley’s Brad Delong correctly called the “killer app” of the railway age: mail order retail, courtesy of Montgomery Ward and Sears Roebuck. And it was also about 50 years from when Thomas Edison threw the switch at the Pearl Street generating plant in 1882 until the unprecedented acceleration of manufacturing productivity through the Great Depression, as documented by Alexander Field, plus the proliferation of electric appliances that transformed home life.

In each case, layers of constructed abstraction concealed the complexities of the underlying technology from its users. Railway Express made shipping goods mindlessly easy for distributors and consumers. Standardization of electricity supply through regional and finally national grids delivered power to the plug with no need to worry about the specifics of voltage, amperage or cycles per second.

So it is now, just 50 years from the invention of the microprocessor, that the complex of digital technologies have matured to the point that — from the point of view of the user — ICT has begun to disappear, as electricity did for our grandparents. And the combination of Open Source software tools and cloud computing resources means that the cost of experimentation for new web services has plummeted even as the extension of broadband internet expands the addressable market by orders of magnitude.

Whatever its failures of corporate culture and leadership, Uber exemplifies the friction-less provision of services that only now can be imagined, developed and deployed at the frontier of the digital economy.

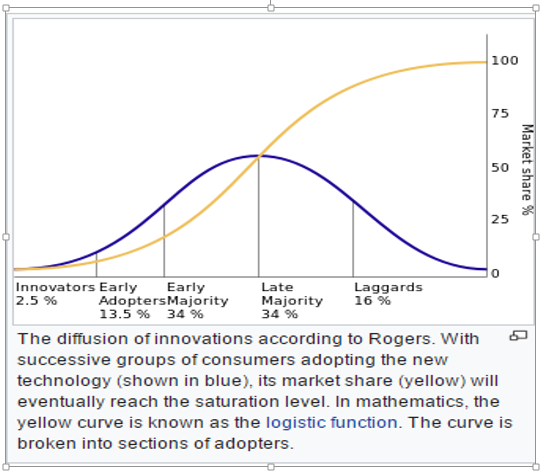

But note: the transformational economic impact of technology does not come as one uniform wavefront. In 1962, Everett Rogers analyzed the “diffusion of technologies” as a process that he mapped to the logistics curve that begins slowly, accelerates to a peak rate of growth and then slows down as the market space becomes saturated.

Chad Syverson of the University of Chicago has spotted a pause in the growth of productivity in the United States during the era of electrification in 1924–1932 that is spookily comparable to what we have been experiencing. Note that this decline in the slope of the curve came exactly when the grid was being built out by the most economically important growth sector of the Roaring Twenties, the electrical utility industry:

IR #2 was not over in 1932. And far from IR #3 being over today, the acceleration of eCommerce, the universality of social media, the deployment of increasingly functional robots, and — above all — the mining of ever bigger data by machine learning algorithms all offer evidence that, 50 years on, we are barely half done.

So, the right question is:

Where Are We in the Diffusion of Digital Technologies?

To this question, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (“OECD”) has provided an answer based on masses of relevant evidence. Two summary charts deliver the central message of the OECD’s working paper, appropriately titled “The Best versus the Rest:

Since the end of the Dotcom/Internet Bubble, across the developed world, the “best” 5% of firms in terms of productivity have maintained historic trend growth in productivity both in manufacturing and service industries, while average productivity of the laggards has stagnated.

Andy Haldane, Chief Economist of the Bank of England, found the same phenomenon when he analyzed the labor productivity of no less than 30,000 British firms over roughly the same period:

A. Haldane, James Meade Lecture, University of Cambridge March 1, 2017

Again, the most productive firms — in both manufacturing and services — have stayed on trend even while the vast majority have have fallen away.

So, the crucial, follow-on question is:

Why Are the Best So Much Better Than the Rest?

The productivity of the best is truly astounding. This chart from Business Insider provides a rough approximation by showing revenue per employee for the top tech firms:

Amazon’s revenues per employee ($475,300 in 2016) is more than twice that of Wal-Mart ($211,200 in the year ended 1/31/2017)

Let’s look first at why the Rest lag. The history of electrification suggests one possible explanation. Before electricity supply was standardized and widely distributed, manufacturing firms needed to install and manage their own generators and motors. Skilled electrical engineers were required to turn frontier invention into useful work.

So it has been in the Age of ICT, from the first deployment of computers and so it remains for those who do yet have broadband access to “the Cloud.” Firms that want the benefits of computing have had to hire their own IT Departments and manage computer operations and application development and deployment. So the first hypothesis is that access to cloud computing through “real” broadband internet (say, 100 megabits per second) will virtualize the underlying technology even as the grid did with electricity.

It is happening, but we are not there yet. One significant indicator that we have a long way to go may be the fact that the U.S. Department of Commerce stopped updating its “national broadband map” after June 30, 2014. The FCC’s “2016 Broadband Progress Report” does offer a map as of December 31, 2014 that provides residential access by broadband speed (minimum advertised speed of 100 mpbs is in the darkest blue):

But, of course, unlike electricity, taking advantage of internet access to basic processing and storage services is not enough. What broadly characterizes the Best is their development and deployment of ways to mine and monetize the data that their business activities generate. And the leader in cloud computing, Amazon Web Services, is responding:

Amazon Web Services provides a broad range of services to help you build and deploy big data analytics applications quickly and easily. AWS gives you fast access to flexible and low cost IT resources, so you can rapidly scale virtually any big data application including data warehousing, clickstream analytics, fraud detection, recommendation engines, event-driven ETL, serverless computing, and internet-of-things processing. With AWS you don’t need to make large upfront investments in time and money to build and maintain infrastructure. Instead, you can provision exactly the right type and size of resources you need to power big data analytics applications. You can access as many resources as you need, almost instantly, and only pay for what you use.

While AWS and its followers, notably Microsoft Azure and Google Cloud, will be helping the Rest to use analytics to refine their business offering and improve their operational efficiency — with benefit to productivity — the Best, the very BEST that is, will stay ahead. For, at the frontier, the Digital Revolution is delivering a new dynamic source of self-sustaining competitive advantage.

“Data Is the Next Intel Inside”

No less than a dozen years ago, with characteristic foresight, Tim O’Reilly recognized that the driving source of value in IT was once again shifting. Over the decade from roughly 1985, value shifted from hardware to software as computers themselves were commoditized. Now, some thirty years later, value is shifting again, from software to data. (For context, see my article on how enterprise software went from being the best place for a VC to invest to one of the worst over the past twenty years Enterprise Software: Death and Transfiguration.)

Data generates business value to the extent that it is mined to extract meaningful and actionable information. This is the sharp end of the Machine Learning juggernaut, where the development of new computational processes generally known as “deep learning” neural networks are doing just that. Practitioners at the frontier, like Yann Lecun of NYU and Facebook, are at pains to counter the renewed hype over Artificial Intelligence that these real achievements have generated. (For those interested in a skeptical take on the first generation of AI hype, see my piece on “Financing the Future” of AI, delivered at the MIT AI Lab in 1982…yes, 35 years ago!) Behind the hype and likely to survive its frustration, machine learning techniques are transforming the economics of production, distribution and consumption.

The more data, the better the algorithms. And the better the algorithms, the better the quality of service offered by Amazon, Facebook or Google. This is the positive feedback law of machine learning. Previous sources of market power have been patents (Xerox), network externalities (IBM) and government regulations and franchises (ATT). All of these still matter, of course, in the age of the internet. But machine learning as a source of competitive advantage adds another, technological driver whereby those whose offerings — for whatever initial reason —achieve market leadership are endowed with an amplifying ability continuously to improve their relative market position.

So here is the double, paradoxical hypothesis that arises from considering the right question about the Productivity Puzzle. The second half of the Digital Revolution (Gordon’s IR #3) will see productivity of the Rest rise. But even as average productivity emerges from its slump, the Best will continue to maintain, perhaps widen further, their already enormous lead.